Code: 55321

An excellent example of a Japanese Kamaikaze Yosegaki Flag.

Although perhaps better described as a good luck flag, professional translation of the hand painted text seriously suggests a Kamaikaze association, or at least a Japanese Naval Aviation Pilot.

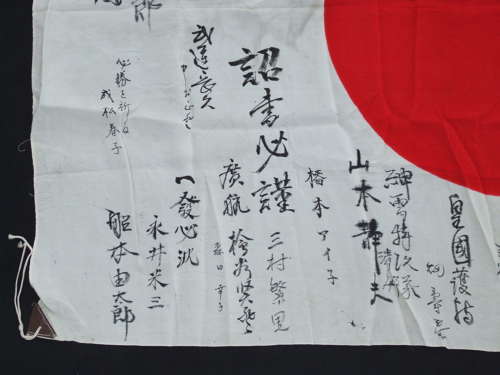

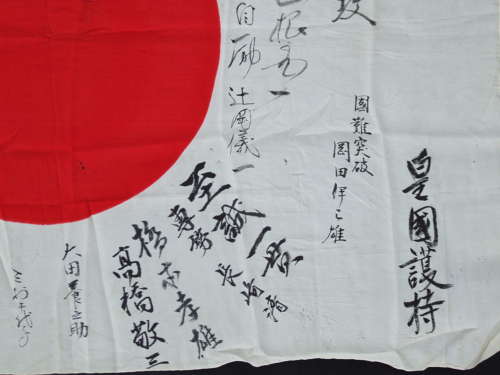

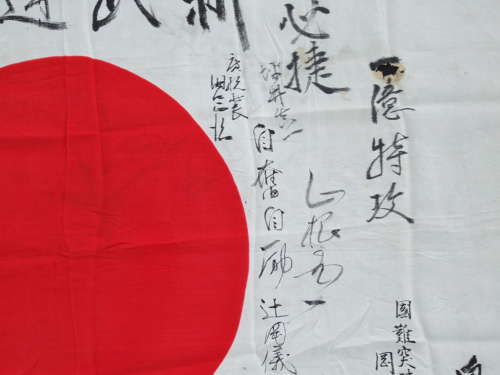

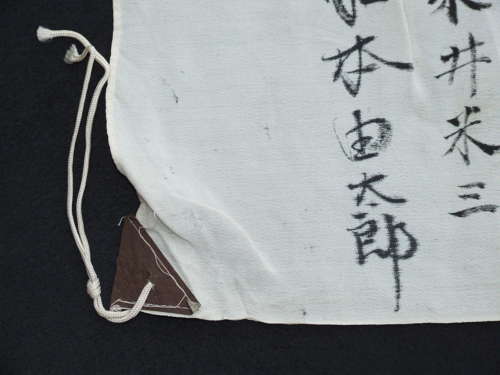

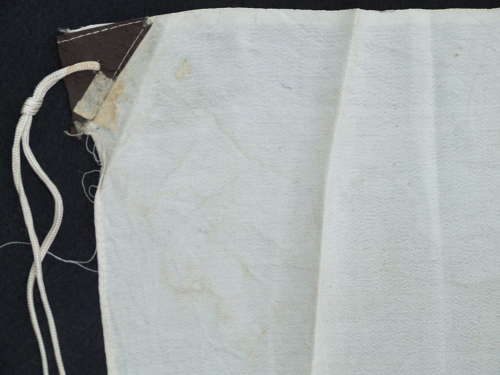

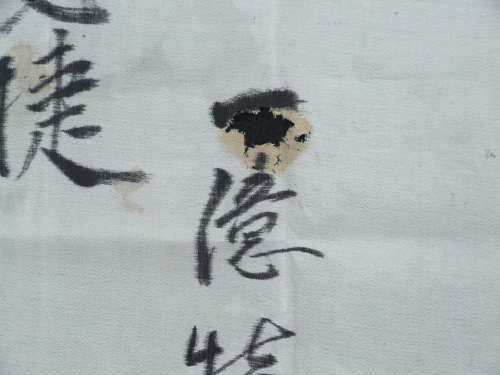

The Flag measures roughly 104 cm x 70cm and is in very good condition with just two stains, one of which has a hole in its centre penetrating the silk. Details of the flag are perhaps best described by the research document which accompanies the flag:

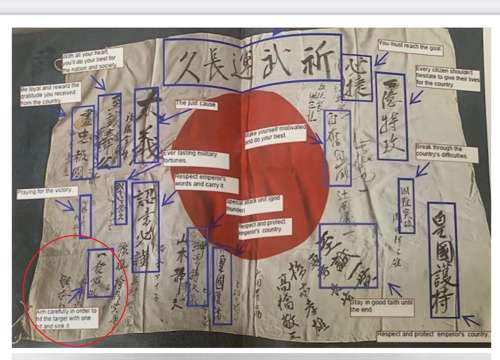

"WW2 Last Stage of War Japanese Kamikaze Yosegaki Flag

A very special Yosegaki flag. The flag most likely belonged to one of the pilots that were intended to take part in special units kamikaze attacks in the last stage of war in the Pacific theatre. The writings also show the dire situation faced by Japanese people at the time.

Some of the slogans translations are:

- “Special Attack Unit God’s Thunder” - the writing mentions the unit 721 that specialised in suicide attacks.

More about the unit here: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/721st_Naval_Air_Group

- “Every citizen shouldn’t hesitate to give their life for the country”

- “Aim carefully in order to hit the target with one shot and sink it”

- “Be loyal and reward the gratitude you’ve received from the country”

- “Stay in good faith until the end”

- “Break through the country’s difficulties”

- “Respect and protect the emperor’s country”

- “Spread the emperor’s words”

- “With all your heart you’ll do your best for the nation and society”

Flag condition itself is very good with only one minor hole to the flag body (see the photos).This is a very special flag showing an inevitable death expected by the person who received this flag and the dire mood of the people who wrote their messages on the flag.

The messages were written in the last stage of war and are focused on dying for the country and encouraging the flag recipient to sink an enemy warship.

The 721st Naval Air Group (第七⼆⼀海軍航空隊, Dai Nana-Futa-Hito Kaigun Kōkūtai) was an aircraft and airbase garrison unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the Pacific campaign of World War II. This air group was organised as specialist in suicide attack. Another known as God thunder Corps (Jinrai Butai).

The Good Luck Flag (寄せ書き⽇の丸, yosegaki hinomaru) was a traditional gift for Japanese servicemen deployed during the military campaigns of the Empire of Japan, most notably during World War II. The flag was typically a national flag signed by friends and family, often with short messages wishing the soldier victory, safety and good luck. Today, hinomaru are used for occasions such as charity and sporting events.

The name 'hinomaru' is taken from the name for the flag of Japan, also known as hinomaru, which translates literally as "circular sun". When yosegaki hinomaru were signed by friends and relatives, the text written on the flag was generally written in a vertical formation radiating out from the central red circle, resembling the sun's rays. This appearance is referenced in the term 'yosegaki' (lit., "collection of writing"), meaning that the term 'yosegaki hinomaru' can be interpreted as a "collection of writing around the red sun", describing the appearance of text radiating outwards from the circle in the centre of the flag.

History

The hinomaru yosegaki was traditionally presented to a man prior to his induction into the Japanese armed forces or before his deployment. The relatives, neighbours, friends, and co-workers of the person receiving the flag would write their names, good luck messages, exhortations, or other personal messages onto the flag in a formation resembling rays dissipating from the sun, though text was also written on any available space if the flag became crowded with messages.

Hinomaru normally featured some kind of exhortation written across the top of the white field, such as bu-un

chō-kyu (武運⻑久, "may your military fortunes be long lasting"); other typical decoration includes medium sized characters along the right or left vertical margin of the flag, typically the name of the man receiving the flag, and the name of the individual or organisation presenting it to him. The text written on the flag was commonly applied with a calligraphy brush and ink. While it was normally the custom to sign only around the red centre of the flag, some examples may be found with characters written upon the red centre as well.

The origin of the custom of writing on flags is unclear, with some debate as to the time period when the custom first began. Some sources indicate that signed flags became part of a soldier's possessions, alongside a "thousand stitch belt" (senninbari), during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), though good luck flags predating the Manchurian Incident (1931) are considered rare. It is generally agreed that most yosegaki hinomaru seen today come from just before or during the period of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).

For the military man stationed far away from home and loved ones, the hinomaru offered communal hopes and prayers to the owner every time the flag was unfolded. It was believed that the flag, with its many signatures and slogans, would provide a combined force or power to see its owner through tough times, as well as reminding the soldier of his duties in the war, with the implication that the performance of that duty meant that the warrior was not expected to return home from battle. Often, departing servicemen would leave behind clipped fingernails and hair, so that his relatives would have something of him in which to hold a funeral.

The belief of self-sacrifice was central to Japanese culture during World War II, forming much of wartime sentiment. It was culturally believed that great honour was brought upon the family of those whose sons, husbands, brothers and fathers died in service to the country and the Emperor, and that in doing one's duty, any soldier, sailor or aviator would offer up his life freely. As part of the cultural samurai or bushido (way of the warrior) code, this worldview was brought forward into twentieth century Japan from the previous centuries of feudal Japan, and was impressed upon twentieth century soldiers, most of whom descended from non-samurai families.

U.S Marines capture a Japanese flag on Iwo Jima

In Sid Phillips's book, You'll Be Sor-ree, Phillips describes the role of Japanese flags in the Pacific War:

"Every Jap seemed to have a personal silk flag with Jap writing all over it and a large meatball in the centre.”

There are numerous books describing hinomaru as souvenirs taken home by U.S. Marines and members of the U.S. Army Infantry. Another example is found in Eugene Sledge's book, With the Old Breed: "The men gloated over, compared, and often swapped their prizes. It was a brutal, ghastly ritual the likes of which have occurred since ancient times on attlefields where antagonists have possessed a profound mutual hatred.”

In a 2008 article in the Monroe News, a World War II veteran spoke of his experiences bringing back a flag from the Pacific War, stating that he did not search every Japanese soldier he shot, as there was usually not enough time; the flag he eventually brought home was found on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

According to his experiences, soldiers did not take home large souvenirs, such as katanas, for fear that someone would steal it, but a flag could be easily concealed. The flag he himself took as a souvenir was in the process of repatriation, with Dr. Yasuhiko Kaji searching for the owner and their family in Japan.

Effort to return flags

The OBON SOCIETY (formerly OBON 2015) is a non-profit affiliate organisation with a mission to return hinomaru to their families in Japan.The society's work has been recognised by Japan's Minister for Foreign Affairs as an "important symbol of reconciliation, mutual understanding, and friendship between our two countries". As of August 2017, the society has returned 108 flags, and has more than 295 other flags they are currently working on returning. On 15 August 2017, the society arranged for Marvin Strombo, a 93 year-old WWII Veteran, to travel back to Japan to return the flag he took to the family of the man who made it. The effort to return the flags is widely seen as a humanitarian act providing closure for family members.